This is a direct reproduction of the original content of ALL HANDS magazine.

©All Hands Magazine, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction by permission only.

Navigate through the "pages" by clicking on the page numbers, next or back links at the bottom of your screen or by clicking the links in the Table of Contents.

Weather Satellites

Pilots taking off from the carriers USS Oriskany (CVA 34) and Constellation (CVA 64) can be sure they will not run smack into a typhoon right after they are launched.

Reason for their certainty is the carriers' use of orbiting weather satellites and an Automatic Picture transmission (APT) system to make use of the available weather data.

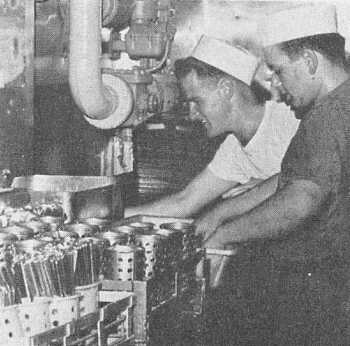

The receivers, called readout stations, are made up of four major components: An antenna control panel, used to TRAIN the ship's antenna on the passing satellite; a receiver to pick up the satellite's transmission; a tape deck, used to record the incoming signal and store it on magnetic tape; and a facsimile unit, which reproduces the original picture taken by the satellite's TV camera.

The ship's receiver picks up signals from two weather satellites, Essa II and Nimbus II, both launched early this year.

A camera inside each satellite takes pictures of the cloud cover below it, and this information, in the form of a radio signal, is relayed to the APT stations aboard the carriers.

Essa II orbits the earth once every hour and 53 minutes, 31 seconds, at an altitude of 750 nautical miles. Its pictures cover an area 1700 nautical miles wide.

Nimbus II, which is in a slightly lower orbit, incorporates an infrared system so it can take pictures at night as well as in daylight.

The satellite's position is radioed to the ship each day by the National Weather Satellite Center in Suitland, Md.

Shipboard aerographers use this information to determine when the satellite will be in receiving range, and then, by means of the directional antenna, track its course. Each of the satellites is within receiving range three times a day; one, on an overhead pass, gives the picture of the ship's immediate operating area, and the other two cover the areas to the east and west.

Once the weather pictures are received and reproduced, they are "gridded" by adding latitude and longitude lines. Then they are given to the forecaster/analyst who uses the weather maps in his daily forecasts.

When Oriskany and Constellation pilots take off, they know what kind of weather they are getting into.

Seventh Fleet Communications

An important element in any naval operation is fast, effective communications. The over-all commander of the operation often is far removed from his deployed forces, sometimes by hundreds or even thousands of miles.

Yet, he must keep, in constant touch with these forces, be kept up-to-date on their movements, and be able to relay to them any late information or changes in plans that might be required.

This basic need for communications is nowhere more apparent than in USS Oklahoma City (CLG 5), flagship for Commander U.S. Seventh Fleet.

To communicate with the forces in the Western Pacific area, this guided missile cruiser-flagship carries one of the most modern communications complexes ever placed on board a naval ship.

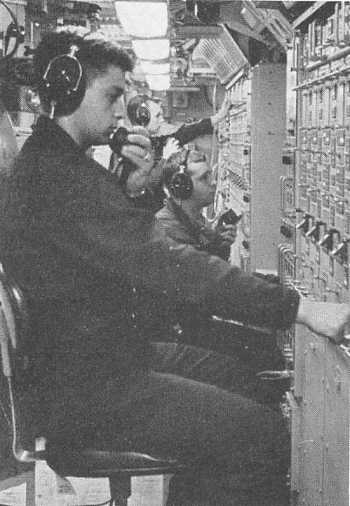

Some 180 major pieces of communication equipment handle the thousands of messages sent daily to and from Commander Seventh Fleet.

This equipment ranges from flaghoist and semaphore, among the oldest forms of naval communications still in use, to the most up-to date cryptographic, teletypewriter and radio equipment available.

More than a dozen radioteletypewriter machines are in continuous operation, carrying data to and from the 175 ships of the Seventh Fleet, as well as keeping the flagship in touch with Pacific Fleet headquarters in Hawaii, and command activities in the continental U.S.

Seventh Fleet ships and shore stations are only minutes away from the flagship, thanks to these communication circuits. This was amply demonstrated off the coast of Vietnam in August 1964. Less than 20 minutes after the destroyers USS Maddox (DD 731) and Turner Joy (DD 951) reported being attacked by North Vietnamese torpedo boats in the Gulf of Tonkin, the Fleet commander was reading the message report more than 2000 miles away.

Messages within the Seventh Fleet normally are relayed through the shore communications stations located at Guam, the Philippines, and Japan. However, ships such as the major communications relay ship USS Annapolis (AGMR 1) are providing a further extension of command into areas where there are no shore-based facilities.

Other communications improvements have taken place aboard the flagship itself. A constant voice radio-telephone circuit allows the Fleet commander or members of his staff to hold conferences with task force commanders who are miles apart on the high seas.

The communication crew also maintains 10 tactical voice circuits. When the various Fleet units are engaged in operations such as shore bombardment, amphibious landings, or anti-air warfare protection off the Vietnam coast, the number of voice circuits often increases to 17.

It takes more than 20 officers and 165 enlisted men to handle the communications job aboard Oklahoma City. Understandable, since she claims to process more messages than any other warship in history.

Sea Survival Course Is Rugged But Popular

The mission was rough, but successful. Now, you're heading home.

All's quiet and serene on the horizon, a setting in distinct contrast to the bursting flak surround ing the plane above target. It's a relief to know there're only a few miles left to fly before sighting the carrier, so you settle back and absorb the impressive vastness of the ocean below.

Suddenly, the jet's instrument panel glows red - a loss of oil pressure. Your speed rapidly decreases. The engine flames out. The radio doesn't respond. The ultimate decision. . . eject!

This possibility is faced by all our naval aviators flying sorties over Vietnam. Some of them encounter the experience.

To prepare the pilot for such a circumstance, whether in war or peace, the Naval Aviation Schools Command at Pensacola places special emphasis on its Sea Survival course.

The student practices freeing himself from a parachute harness in water and boarding various life rafts.

In full flight gear, he slides down a 50-foot slanting cable into the water. The effect is similar to a parachute landing. The TRAINee then releases himself from the harness while being towed by boat at about seven knots.

He must then swim 300 yards from a whaleboat to an LCM and board it via its Jacobs ladder.

Once be has mastered the escape techniques, his final test is bow to, remain alive.

Four to five hours are spent in a PK2 one-man life raft where the student uses survival equipment be became familiar with in the classroom. He prepares fresh water from the sea using a de-salting kit and solar still and uses signal mirrors, day and night flares, shark chaser and dye markers.

This TRAINing, coupled with man's natural instinct of self-preservation, increases the pilots' confidence in their ability to survive at sea should ever it become necessary to ditch or eject over water.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 |

| 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 |

Page 40